It’s the 150th Anniversary of the Golden Spike: Learn 12 Interesting Facts about How the Railroad Changed Utah

Contributed By Trent Toone, Deseret News

The joining of the rails at Promontory, Utah, is photographed May 10, 1869. The photo is taken from the original glass plate from the Oakland Museum.

Article Highlights

- The 150th anniversary of the golden spike is May 10, 2019.

- The union of the railroads enabled easier travel.

- The Salt Lake Valley grew in population and prosperity after the railroad.

“[The railroad] changed the dynamics of time and space. It introduced modes of travel. For Latter-day Saints, they hoped it would break down some of the prejudices against them. They hoped it would help with missionary work and bring some prosperity to the Church and community in the Great Basin.” —Brent M. Rogers, Church History Library historian

Related Links

In the late 1860s, a misconception existed among most Americans that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints didn’t want the transcontinental railroad passing through Utah.

The common belief, which stemmed in part from plural marriage issues, was that Latter-day Saints preferred insularity and isolation from the rest of the world.

An 1867 New York Tribune article reported, “The Mormon difficulty, which has perplexed us for so many years is rapidly solving itself … [the railroad] will see the polygamists of the great plains quietly absorbed by a law-abiding and industrious race of new settlers.”

On the contrary, President Brigham Young understood the economic benefits of a national rail line and how it would bless the Saints. He dispelled the myth in an 1868 discourse.

“As for this people not wanting the railroad, why there is no people in the world that will take the matter into consideration but will see at once that we need it more than any other portion of the community,” the Church leader said. “I want this railroad to come through this city and to pass on the south shore of the lake. We want the benefits of this railroad for our emigrants, so that after they land in New York they may get on board the cars and never leave them again until they reach this city.”

The misconception was one of 12 interesting notes shared by Brent M. Rogers and Brett D. Dowdle, historians at the Church History Library, ahead of the upcoming 150th Golden Spike Anniversary on May 10.

The completion of the transcontinental railroad was “revolutionary” and “transformative” for Utah and the Church, the historians agreed.

“It was transformative in basically every aspect of life,” Dowdle said. “It basically changes everything.”

“Maybe the word ‘revolutionary’ isn’t the best word, but I tend to think of it in those terms,” Rogers said. “It changed the dynamics of time and space. It introduced modes of travel. For Latter-day Saints, they hoped it would break down some of the prejudices against them. They hoped it would help with missionary work and bring some prosperity to the Church and community in the Great Basin. I think it does a lot of that. It completely changes the game.”

Latter-day Saint lobbyists

The Latter-day Saints began lobbying Congress for a railroad to pass through Utah as early as 1852, more than 15 years before the driving of the golden spike, Rogers said.

“We never traveled a day,” Brigham Young told a Salt Lake Tabernacle audience in 1870. “And I can call my brethren to witness the truth of what I assert, from the time we crossed the Missouri to this point, but what we were looking for a track for the railroad, and we had not been here long before we petitioned Congress to build a railroad as well as for a government.”

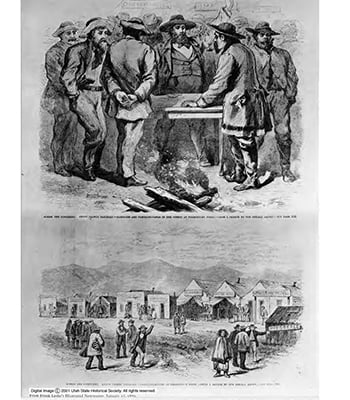

A view at Promontory, Utah, May 10, 1869, during the “Last Spike” ceremony when rails of the Central Pacific (now Southern Pacific) and the Union Pacific were joined to complete the first transcontinental railroad. The picture is taken from the U.P. locomotive No. 119, looking westward, and shows the four companies of the 21st Infantry in formation alongside the track of Central Pacific’s locomotive “Jupiter” with tent-buildings. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

There’s an extensive history during the 1850s when Brigham Young is writing to Stephen A. Douglas, an influential senator who has important connections with railroad interests, Rogers said.

“He’s trying to convince him that the best route is through Provo Canyon and then up through Salt Lake,” Rogers said. “Some of the earliest railroad surveyors come through and see that the route ultimately taken is the best route.”

On April 8, 1869, one month before the transcontinental line is finished, President Young said the railroad would bless the Church.

“It is said the railroad was built expressly to overthrow the Latter-day Saints and the work of God on the earth,” he said. “But it will promote His work. It is put into our hands, we thank Him for it, and we say God bless those who built it; and God bless every good man and everyone who speaks well of Zion.”

Construction

The Latter-day Saints had an immense role in building the transcontinental railroad, Dowdle said.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper drawings represent the atmosphere, particularly the gambling crowds, at Promontory, Utah, during the joining of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroad in 1869. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

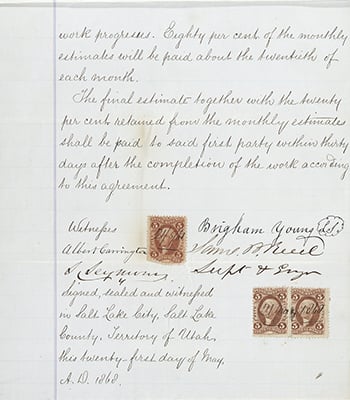

In May 1868, the railroad companies approached President Young about getting men to work on the railroad. They went back and forth and finally signed a contract. The original contract with Brigham Young’s signature is part of his Office Papers collection in the Church History Library, Dowdle said.

Latter-day Saint railroad workers didn’t always get paid on time, but it was ultimately a blessing, as recorded in an 1868 Payson Latter-day Saint Ward history.

“Times changed very much for the better during the autumn and winter,” the entry reads. “The construction of the great overland railroad furnished remunerative employment to hundreds of our people and money was plenty in every man’s pockets and all kinds of commodities were cheap and abundant.”

Pioneer Mary L. Ahlstrom wrote about her father working on the railroad.

“That summer [1868] lots of men were called to go out in Echo Canyon to work on the railroad, and papa went,” Ahlstrom wrote. “He came home a few days and had money, so we got some flour and shoes and cloth to make some clothes. He went back again to work till winter came on so they couldn’t work. In 1869 the train came to Ogden Weber Canyon. Now we had better times. That fall I got my first stove.”

Positive reaction

The general reaction by Latter-day Saints to the coming of the railroad was positive, Rogers and Dowdle agreed.

President George A. Smith, then a member of the First Presidency, reacted to the May 10 wedding of the rails this way.

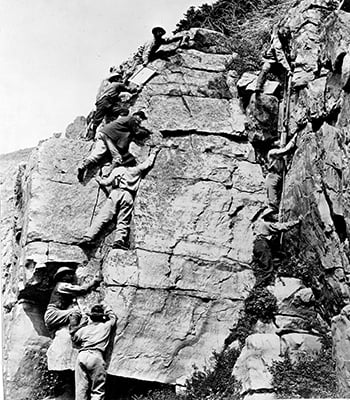

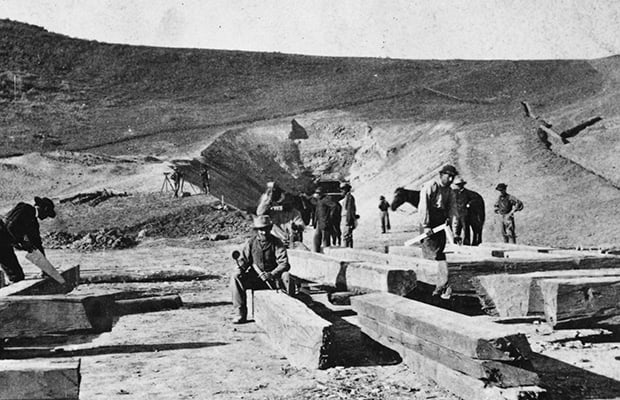

Latter-day Saints survey during construction of the transcontinental railroad in the Uintah Mountains of Utah for the Union Pacific Railroad. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

“We have every reason to suppose that, as a people, by being better known, we shall be better understood,” President Smith said.

Under the headline “The Completion of the Pacific Railroad” the Deseret News published, “To the people of Utah—the Latter-day Saints—the completion of the Union Pacific Railroad is a matter of more significance and interest than to any other portion of their fellow citizens of the Union; and while they rejoice with them at its completion and at the prospect of the increased prosperity it will bring to the nation at large, they rejoice more than all in the fact, that now the dreams of the ancient prophet, who spake about the swift gathering of the people from the nations in the latter days when the ‘Great Highway’ should be thrown up, will be realized. They acknowledge the hand of the Almighty in all movements affecting the interests and welfare of mankind at large, and believe that the construction of the Great Pacific Railroad will prove a mighty instrument in His hands in accomplishing His purposes and in accelerating the progress and triumph of His cause and kingdom upon the earth.”

Economic concerns

Despite all the positives, there was some lingering tension and fear about unwanted elements coming in and disrupting their community. The Church also worried about the increase of drinking, gambling, and prostitution, Rogers said.

“How do we take advantage of the new opportunities of the railroad but keep at bay the influx of outsiders?” Rogers said. “That leads to some troubles among the Church itself.”

During the late 1860s, a group of Latter-day Saints became dissatisfied with President Young and the Church’s economic power, and some left the Church. This development is known as the “Godbeites Movement,” Dowdle said.

To become a self-sustaining community, President Young encouraged the Saints to reinvest in themselves. One project designed to help with this was the founding of Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution (ZCMI) in 1868.

“We will produce our own goods, we will buy from each other, and we will be a self-sustaining community,” Dowdle said. “This is in direct response to some of the potential threats coming from the railroad. It ends up culminating in these challenges with the Godbeites. It’s an interesting little episode.”

A railroad car and maintenance crew. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

Paid in iron

When the Union Pacific Railroad didn’t have the cash to pay workers, it resolved the issue by giving the Church excess iron and rail for building the Utah Central line, Rogers said.

Seven days after the golden spike ceremony in Promontory, Box Elder County, the Church broke ground on the Utah Central Railroad. Within a year, they had tied Salt Lake into the transcontinental line and started to create a network of tracks in the Utah Territory.

“We are getting iron in lieu of money, and we are going to place it where it will do us good,” President Young said on May 17, 1869. “We have felt somewhat to complain of the Union Pacific Railroad Company for not paying us for the work we did in grading so many miles of their road. But let me say, if they had paid us according to our agreement, this road would not have been graded, and this track would not have been laid today. It is all right.”

The new lines were instrumental in hauling more materials for construction on the Salt Lake Temple.

“It greatly accelerates the work on the temple,” Rogers said.

Women

Women played a role in construction of the railroad, Rogers noted.

John T. Gerber, a cook in one of the railroad camps, occasionally wrote in his journal that women sometimes visited the camps to bring homemade clothes, goods, conversation, and comfort to the men.

“Whether it was wives, sisters, or friends, they came in to boost the spirits of the Latter-day Saint men,” Rogers said. “These are men who have left wives and families in the valley. … It was a sacrifice on both the male laborers as well as the women, and the women … they’re doing a good job of visiting and making sure the men have some company from time to time. I think that’s a valuable and interesting side to the story.”

The iron spike ceremony

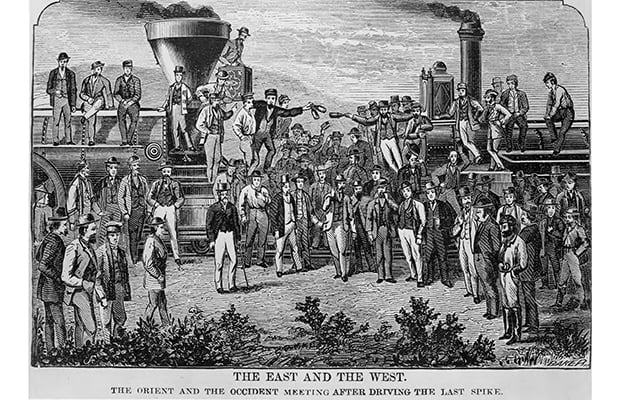

For many, the momentous celebration of the golden spike ceremony was captured in an iconic photograph that depicts a large group standing with two engines facing each other.

But no Latter-day Saints were likely present on that historic day, May 10, 1869, Dowdle said.

The Church and community held their own ceremony on January 10, 1870, to celebrate the Utah Central Railroad line from Ogden to Salt Lake. It’s significant because it’s an event that brought everyone in the community—members and nonmembers—together, Dowdle said.

“This is one of those rare moments in Utah history where you end up having people that don’t necessarily get along well come together in celebration,” Dowdle said.

President Brigham Young’s signature on a contract with the Union Pacific Railroad. The document is among the Brigham Young Office Papers at the Church History Library.

In his journal, Elder Wilford Woodruff described the scene in what he termed “a great day in Utah.”

“Some 12 to 15,000 of the inhabitants of the city of Salt Lake and surrounding country of men and women and children assembled around the railroad depot to celebrate the building of the Utah Central Railroad and to see the last rail laid and the last spike driven by President Brigham Young. This railroad was built by the hard-laboring men of the Latter-day Saints from Ogden to Salt Lake City, about 40 miles distant,” the Church leader wrote. “There were present in the assembly bands of music from the city, Camp Douglas, and many others. There were present on the stand the First Presidency, the Twelve Apostles, the officers of the Union and Central Pacific Railroad and of the Utah Central Railroad with many invited guest[s] including the officers of Camp Douglas.

“The last spike was driven by President Young. A large steel mallet was used on the occasion. … There was engraved a beehive surmounted by the inscription ‘Holiness to the Lord.’ Underneath the beehive were the letters U.C.R.R., the spike made of homemade iron.

“Just before the ceremony of laying the last rail commenced, the sun, which during the whole day had been completely concealed by clouds, burst forth with unclouded brilliancy as if determined to enhance the general joy by his genial rays. After the performance … a salute of 37 guns was given.”

To see the Church leaders and Army officers come together at the time was significant due to tension from issues like plural marriage and recent events like the Utah War, Mountain Meadows Massacre, Bear River Massacre, and the Blackhawk War, the historians said.

“There are a number of reasons why none of these people should be sitting on a stand together, but this event, which they are trying to mirror after Promontory Point, brings everyone together for a couple of hours,” Dowdle said.

“It truly transcends the major differences that these people have with one another,” Rogers said. “And they’re all really on board.”

Immigration season

The transcontinental railroad also dramatically changed cross-country travel, Dowdle said.

Before the wedding of the rails in Utah, European immigrants sailed across the ocean and had to leave between April and June for wagons and handcarts to reach Utah before any early winter storms.

With the completed railroad, months of hardships, danger, and occasional deaths on the plains were reduced to 7–10 days of travel on a train.

“What the railroad does is it extends the immigration season throughout the entire year rather than condensing it down to a few months,” Dowdle said.

An excerpt from Ahlstrom’s autobiographical sketch illustrates one glimpse of difficulties of overland wagon travel during the 1850s.

“On and on we went; we had two deaths on the road, a baby and an old man. They were buried by the road side,” the sketch reads. “But the last days before we got there [Salt Lake Valley] we had a hard struggle up the big mountain. We had to stop every few minutes and pick up rocks and put them under the wagon wheels so they wouldn’t roll back. The mountain was so steep the oxen couldn’t hold them. The mountain was five miles high up hill, and I carried my baby all the way.”

Contrast that view with the comfort of the new railroad, Rogers said.

“With the railroad, you’re sitting back as the train takes you up [the mountain], and it finds the cuts and valleys, they create tunnels, but you don’t have to go five miles up the mountain,” Rogers said. “Instead of several months of hard walking, deaths along the way, you have to deal with finding food for a week. The railroad transforms travel and mobility.”

In the first six months after the transcontinental line is completed, nearly 2,500 Latter-day Saints came to the Salt Lake Valley, Rogers said.

“That’s a pretty significant number when you’ve probably had maybe a few hundred that would come in a typical, overland summer,” Rogers said. “So you can see the numbers that could be accommodated on the rails and the ease and quickness with which they come.”

Utah’s population

In 1860, the U.S. census records Salt Lake City’s population at 8,236.

In 1870, one year after the completion of the transcontinental railroad, the population was 12,854.

Ten years later in 1880, the population nearly doubled to 20,768.

By 1890, the population was 44,843.

“That’s a real testament to the transcontinental railroad and what it does,” Dowdle said.

Pleasure rides

While the railroad increased economic growth and ability to travel, it also allowed for pleasure excursions.

Vienna Jacques, an early Latter-day Saint convert, walked or traveled by wagon from Boston to Ohio, Missouri, Illinois, and finally to Utah as she followed the Church over her lifetime.

As an old woman in the 1870s, she enjoyed riding the train from Salt Lake to Provo to festivals where she spoke to large groups about her pioneer experiences, Rogers said.

“I sit here and imagine someone like Vienna, who walked these thousands and thousands of miles, following her faith,” Rogers said. “Then with the advent of the railroad and coming of the train, she gets to experience that. How much of a joy would that have been to travel and get to share her experiences and faith with other Latter-day Saints? It’s something I thought was pretty cool.”

Educational opportunities

The railroad also opened educational doors for folks in Utah, Dowdle said.

Beginning in the late 1860s, President Young and other Latter-day Saint families sent children back East to receive higher education.

“You have men getting law degrees and women getting medical degrees,” Dowdle said. “This facilitates not only the ability for the population to grow, but it facilitates the ability of the population to get access to better knowledge and collegiate education. Many of those people come back and benefit the territory in terms of providing additional educational training. … All of this is possible because travel is easier. If there isn’t a transcontinental railroad, the likelihood of those people getting college degrees is very slim.”

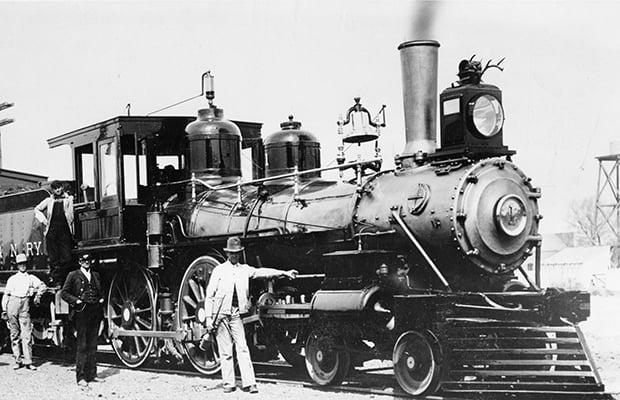

Central Pacific locomotive No. 60, “Jupiter,” is photographed at Promontory Summit, May 10, 1869, after the driving of the last spike. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

Trestle Union Pacific No. 119 drives on the high trestle on the east slope of the North Promontory Range in 1869. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

A copy of an old woodcut shows the juncture of the first transcontinental rail line at Promontory, Utah, May 10, 1869. Central Pacific’s “Jupiter” is at left, and U.P.’s No. 119 is at right. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

Promontory Point Railroad Station, Southern Pacific, circa 1920. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

The Utah Central Railroad Depot at Provo, Utah, is photographed in 1887. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

Tunnel No. 2 is built at the head of Echo Canyon, Utah, during construction of the Union Pacific Railroad. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

Railroad No. 60, “Jupiter,” was used at the driving of the golden spike in Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

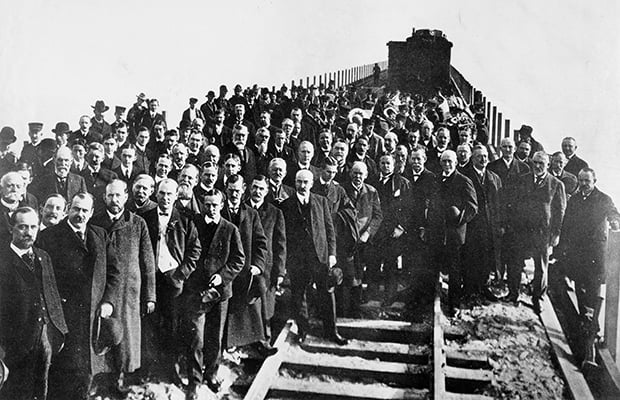

Officials pose for a photograph at the celebration of the completion of Lucin Cutoff on Thanksgiving, November 26, 1903. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

Performers pose for a reenactment photo at the Golden Spike commemorative ceremony in Brigham City, Tuesday, May 10, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell, Deseret News.

The No. 119 engine is photographed Monday, May 10, 2010, as the Golden Spike National Historic Site celebrated the 141st anniversary of the day the country was united by rail. Photo by Scott G. Winterton, Deseret News.

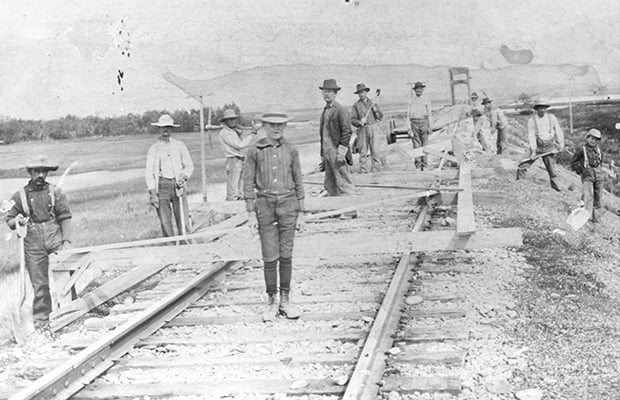

Workers, including men and boys, work on a Central Pacific Railroad grade and bridge over Bear River at Corinne, looking east. The Wasatch Range can be seen in the background. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

This photo shows a different view of the crowd gathered at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.